Jonathan HeadSouth East Asia correspondent

AFP via Getty Images)

AFP via Getty Images)When insurgents finally gained control of the town of Kyaukme – on the main trade route from the Chinese border to the rest of Myanmar – it was after several months of hard fighting last year.

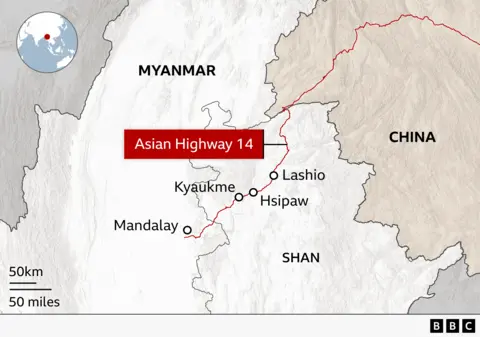

Kyaukme straddles Asian Highway 14, more famous as the Burma Road during World War Two, and its capture by the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) was seen by many as a pivotal victory for the opposition. It suggested that the morale of the military junta which had seized power in 2021 might be crumbling.

This month, though, it took just three weeks for the army to recapture Kyaukme.

The fluctuating fate of this little hill town is a stark illustration of how far the military balance in Myanmar has now shifted, in favour of the junta.

Kyakme has paid a heavy price. Large parts of the town have been flattened by daily air strikes carried out by the military while it was in the hands of the TNLA. Air force jets dropped 500-pound bombs, while artillery and drones hit insurgent positions outside the town. Much of the population fled the town, though they are starting to return now the military has retaken it.

“There is heavy fighting going on every day, in Kyaukme and Hsipaw,” Tar Parn La, a spokesman for the TNLA, told the BBC earlier this month. “This year the military has more soldiers, more heavy weapons, and more air power. We are trying our best to defend Hsipaw.”

Since the BBC spoke to him the junta’s forces have also retaken Hsipaw, the last of the towns captured by the TNLA last year, restoring its control over the road to the Chinese border.

These towns fell primarily because China has thrown its weight behind the junta, backing its plan to hold an election in December. This plan has been widely condemned because it excludes Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy, which won the last election but its government was ousted in the coup, and because so much of Myanmar is in a state of civil war.

That is why the military is currently trying to take back as much lost territory as it can, to ensure the election can take place in these areas. And it is enjoying more success this year because it has learned from its past failures, and acquired new and deadly technology.

In particular, it has responded to the early advantage enjoyed by the opposition in the use of inexpensive drones, by buying thousands of its own drones from China, and training its forward units how to use them, to deadly effect.

It is also using slow and easy-to-fly motorised paragliders, which can loiter over lightly-defended areas and drop bombs with high accuracy. And it has been bombing relentlessly with its Chinese and Russian supplied aircraft, causing much higher numbers of civilian casualties this year. At least a thousand are believed to have been killed this year, but the total is probably higher.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesOn the other side, the fragmented opposition movement has been hampered by inherent weaknesses.

It comprises hundreds of often poorly-armed “people’s defence forces” or PDFs, formed by local villagers or by young activists who fled from the cities, but also seasoned fighters from the ethnic insurgent groups who have been waging war against the central government for decades.

They have their own agendas, harbouring a deep mistrust of the ethnic Burmese majority, and they do not recognise the authority of the National Unity Government which was formed from the administration ousted by the 2021 coup. So there is no central leadership of the movement.

And now, more than four years into a civil war that has killed thousands and displaced millions, the tide is turning once again.

How the junta recouped its losses

When an alliance of three ethnic armies in Shan State launched their campaign against the military in October 2023 – calling it Operation 1027 – armed resistance to the coup had been going on in much of the country for more than two years, but making little progress.

That changed with Operation 1027. The three groups, calling themselves the Brotherhood Alliance – the Ta’ang National Liberation Army, the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army and the Arakan Army – had prepared their attack for months, deploying large numbers of drones and heavy artillery.

They caught military bases off-guard, and within a few weeks had overrun around 180 of them, taking control of a large swathe of northern Shan State, and forcing thousands of soldiers to surrender.

These stunning victories were greeted by the broader opposition movement as a call to arms, and PDFs began attacks in their own areas, taking advantage of low military morale.

As the Brotherhood Alliance moved down Asian Highway 14, towards Myanmar’s second-largest city of Mandalay, there was open speculation that the military regime might collapse.

That did not happen.

Getty Images

Getty Images Getty Images

Getty Images“Two things were overstated at the start of this conflict,” says Morgan Michaels, a research fellow at the International Institute of Strategic Studies.

“The three Shan insurgent groups had a long history of working together. When other groups saw their success in 2023, they then synchronised their own offensives, but this was misread as some sort of unified, nationwide opposition steaming towards victory. The second misreading was how bad military morale was. It was bad, but not to the extent where command and control was breaking down.”

The junta responded to its losses in late 2023 by starting a forced conscription drive. Thousands of young Burmese men chose to flee, going into hiding or exile overseas, or joining the resistance.

But more than 60,000 joined the army, replenishing its exhausted ranks. While inexperienced, they have made a difference. Insurgent sources have confirmed to the BBC that the new recruits are one of the factors, together with the drones and air strikes, which have turned the tide on the battlefield.

Drones have given the junta a decisive advantage, reinforcing its supremacy in the air, according to Su Mon, a senior analyst at the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (Acled), which specialises in gathering data on armed conflicts. She has been monitoring the military’s use of drones

“The resistance groups have been telling us that the almost constant drone attacks have killed many of their solders and forced them to retreat. Our data also shows that military air strikes have become more accurate, possibly because they are being guided by drones.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMeanwhile, she says tighter border controls and China’s ban on the export of dual-use products are making it harder for the resistance groups to get access to drones, or even the components to assemble their own drones.

Prices have risen steeply. And the military has much better jamming technology now, so many of their drones are being intercepted.

A war on many fronts

The TNLA is not the only ethnic army which is retreating. In April, after strong Chinese pressure, another of the groups in the Brotherhood Alliance, the MNDAA, abandoned Lashio, previously the headquarters of the military in Shan State and a much-heralded prize when the insurgents captured it last year.

The MNDAA has now agreed to stop fighting the junta. And the most powerful and best-armed of the Shan insurgent groups, the UWSA, has also buckled to Chinese demands and agreed to stop supplying weapons and ammunition to other opposition groups in Myanmar.

These groups operate along the border and need regular access to China to function. All China needed to do was close border gates and detain a few of their leaders to get them to comply with its demands.

Further south, in Karen State, the junta has regained control of the road to its second most important crossing on the border with Thailand.

The insurgent Karen National Union, which overran army bases along the road a year and a half ago, blames the new conscripts, new drones and betrayal by other Karen militia groups for its losses. It has even lost Lay Kay Kaw, a new town built with Japanese funding in 2015 for the KNU, at a time when it was part of a ceasefire agreement with the central government.

In neighbouring Kayah, where a coalition of resistance groups has controlled most of the state for two years, the military has retaken the town of Demoso, and the town of Mobye, just inside Shan State. It is also advancing in Kachin State in the north, and in contested areas of Sagaing and Mandalay.

However, there are many parts of Myanmar where the junta has been less successful. Armed resistance groups control most of Rakhine and Chin States, and are holding the military at bay, and even driving it back in places.

One factor in the military’s recent victories is that it is concentrating its forces only in strategically important areas, Morgan Michaels believes, like the main trade routes, and towns where it would like to hold the election.

Tellingly Kyaukme and Hsipaw are both designated as places where voting is supposed to take place. The regime has acknowledged that voting will not be possible in 56 out of Myanmar’s 330 townships; the opposition believes that number will be much higher.

‘China opposes chaos’

China’s influence over the ethnic armies on its border could have stopped them mounting the 1027 operation two years ago. That it chose not to is almost certainly down to its frustration then over the scam centres which had proliferated in areas controlled by clans allied to the junta. The Brotherhood Alliance made sure shutting down the scam centres was at the top of its list of goals.

Today, though, China is giving its wholehearted backing to the junta. It is promising technical and financial aid for the election, and has given visible diplomatic support, arranging two meetings this year between the junta leader Min Aung Hlaing and Xi Jinping. This despite China’s unease about the 2021 coup, and its hugely destructive consequences.

“China opposes chaos and war in Myanmar,” said Foreign Minister Wang Yi in August, which more or less sums up its concerns.

“Beijing’s policy is no state collapse,” Mr Michaels says. “It has no particular love for the military regime, but when it looked like it might teeter and fall, it equated that with state collapse, and stepped in.”

China’s interests in Myanmar are well-known. They share a long border. Myanmar is seen as China’s gateway to the Indian Ocean, and to oil and gas supplies for south-western China. Many Chinese companies now have big investments there.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesAnd with no other diplomatic initiatives making any headway, China’s choice, to bolster the military regime through this election, is likely to be endorsed by other countries in the region.

But even China will find it hard to end the war The devastation and human suffering inflicted by the military on the people of Myanmar have left a legacy of grievances against the generals which may last generations.

“The military has burned down 110 or 120,000 houses just across the dry zone,” Mr Michaels says.

“The violence has been immense, and there are few people who have not been touched by it. That’s why it is difficult to foresee a political process right now. Being forced into ceasefire because you literally cannot hold your front lines is one thing, but political bargaining for peace still seems very distant.”