Scientists are trained to thoroughly investigate their new ideas. Sometimes, however, their preliminary research can go down strange rabbit holes, leading to interpretations of evidence that are, well, misguided. In reporting on emerging science for 180 years, Scientific American has published straight accounts that were considered legitimate at the time but today seem quaint, quizzical, ridiculous—or, sometimes, prophetic. That’s how science works. It evolves. As experts learn more in any given discipline, they revise theories, conduct new experiments and recast former conclusions. SciAm editors and writers have dutifully reported on it all, leaving us with some fun accounts from science history, here for you to enjoy.

Know What? Your Phone Can Send Photos

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

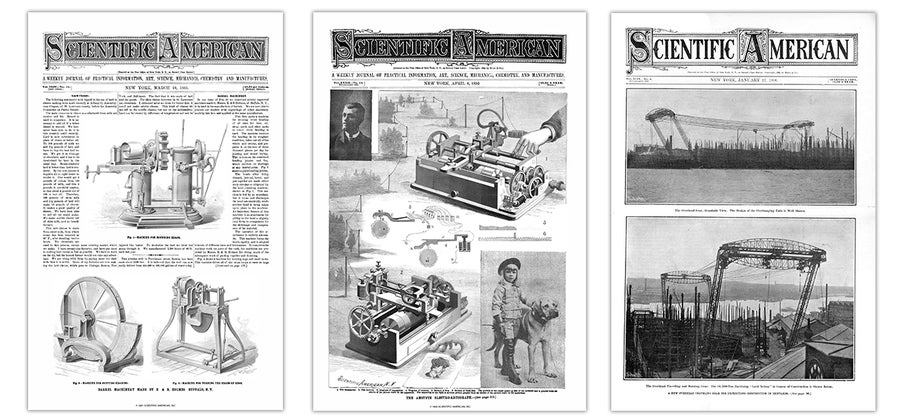

April 6, 1895

“When the telephone was introduced to the attention of the world, and the human voice was made audible miles away, there were dreamy visions of other combinations of natural forces by which even sight of distant scenes might be obtained through inanimate wire. It may be claimed, now, that this same inanimate wire and electrical current will transmit and engrave a copy of a photograph miles away from the original. The electro-artograph, named by its inventor, Mr. N. S. Amstutz, will transmit copies of photographs to any distance, and reproduce the same at the other end of the wire, in line engraving, ready for press printing.” —“The Amstutz Electro-Artograph,” in Scientific American, Vol. LXXII, No. 14, page 215; April 6, 1895

Steam Boilers Are Exploding Everywhere

March 19, 1881

“The records kept by the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company show that 170 steam boilers exploded in the United States last year, killing 259 persons and injuring 555. The classified list shows the largest number of explosions in any class to have been 47, in sawing, planing and woodworking mills. The other principal classes were in order: paper, flouring, pulp and grist mills, and elevators, 19; railroad locomotives and fire engines, 18; steamboats, tugboats, yachts, steam barges, dredges and dry docks, 15; portable engines, hoisters, thrashers, piledrivers and cotton gins, 13; ironworks, rolling mills, furnaces, foundries, machine and boiler shops, 13; distilleries, breweries, malt and sugar houses, soap and chemical works, 10.” —“Whose Boilers Explode,” in Scientific American, Vol. XLIV, No. 12, page 176; March 19, 1881

Want to Crack Open a Safe? Try Nitroglycerin

January 27, 1906

“Today the safe-breaker no longer requires those beautifully fashioned, delicate yet powerful tools which were formerly both the admiration and the despair of the safe manufacturer. For the introduction of nitroglycerine, ‘soup’ in technical parlance, has not only obviated onerous labor, but has again enabled the safe-cracking industry to gain a step on the safe-making one. The modern ‘yeggman,’ however, is often an inartistic, untidy workman, for it frequently happens that when the door suddenly parts company with the safe it takes the front of the building with it. The bombardment of the surrounding territory with portions of the Farmers’ National Bank seldom fails to rouse from slumber even the soundly-sleeping tillers of the soil.” —“The Ungentle Art of Burglary,” in Scientific American, Vol. XCIV, No. 4, page 88; January 27, 1906

Japanese Tissues Surprise Americans

June 19, 1869

“The Japanese dignitaries, says the Boston Journal of Chemistry, who recently visited this country under the direction of Mr. Burlingame, were observed to use pocket paper instead of pocket handkerchiefs, whenever they had occasion to remove perspiration from the forehead, or ‘blow the nose.’ The same piece is never used twice, but is thrown away after it is first taken in hand. We should suppose in time of general catarrh, the whole empire of Japan would be covered with bits of paper blowing about. The paper is quite peculiar, being soft, thin, and very tough.” —“Pocket Paper,” in Scientific American, Vol. XX, No. 25, page 391; June 19, 1869

Poor Pluto Is 10 Times Smaller Than Thought

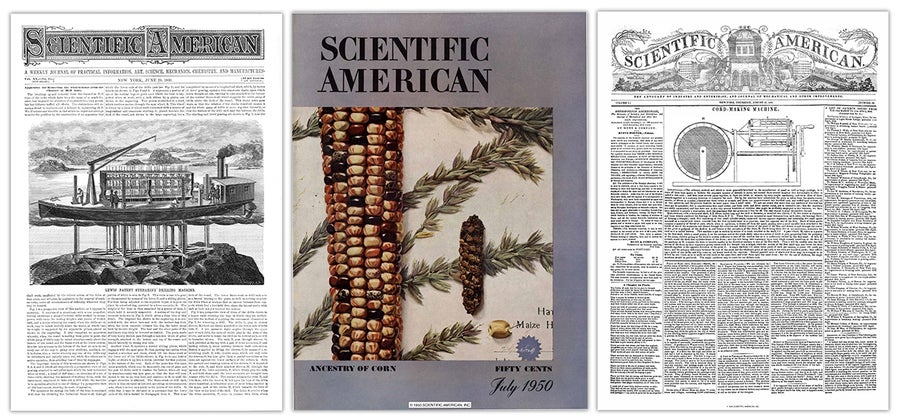

July 1950

“The outermost planet of the solar system has a mass 10 times smaller than hitherto supposed, according to measurements made by Gerard P. Kuiper of Yerkes Observatory with the 200-inch telescope on Palomar Mountain. On the basis of deviations in the path of the planet Neptune, supposedly caused by Pluto’s gravitational attraction, it used to be estimated that Pluto’s mass was approximately that of the earth. Kuiper was the first human being to see the planet as anything more than a pinpoint of light. He calculated that Pluto’s diameter is 3,600 miles, and its mass is one tenth of the earth’s. It leaves unsolved the mystery of Neptune’s perturbations, which are too great to be accounted for by so small a planet as Pluto.” —“Pluto’s Mass,” in Scientific American, Vol. 183, No. 1, page 28; July 1950

Astronomers Fail to Find Factories on the Moon

August 27, 1846

“By means of a magnificent and powerful telescope, procured by Lord Ross, of Ireland, the moon has been subjected to a more critical examination than ever before. It is stated that there were no vestiges of architectural remains to show that the moon is or ever was inhabited by a race of mortals similar to ourselves. The moon presented no appearance that it contained anything like the green-field and lovely verdure of this beautiful world of ours. There was no water visible—not a sea, or a river, or even the measure of a reservoir for supplying a factory—all seemed desolate.” —“The Moon” in Scientific American, Vol. I, No. 49, page 2; August 27, 1846

Widespread Layoffs for Horses

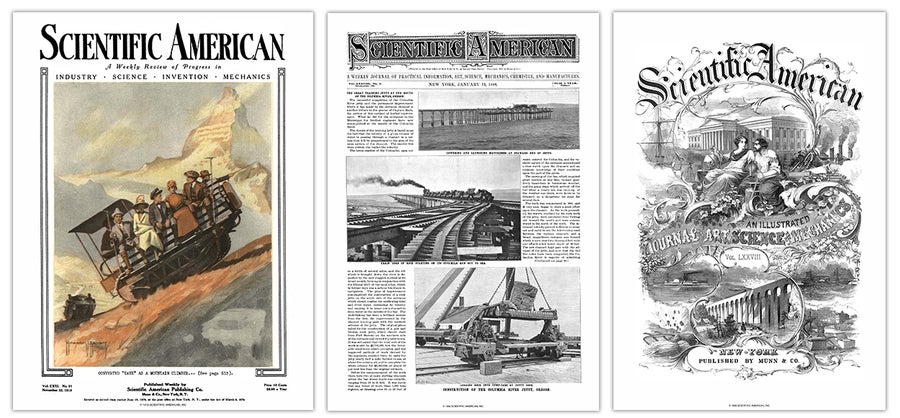

November 22, 1919

“Professional horse-breeders still boost for the business; but they are merely whistling to keep up their courage. The days of the horse as a beast of burden are numbered. The automobile is taking the place of the carriage horse; the truck is taking the place of the dray horse; and the farm tractor the place of the farm horse. Nor is there any cause to bemoan this state of affairs. We all admit that the horse is one of the noblest of animals; and that is a very good reason why we should rejoice at his prospective emancipation from a life of servitude and suffering. That, of course, is the humanitarian side of it; the business side is more to the point: the machine is going to do the hard work of the world much easier and much cheaper than it ever has been done. At least 50 percent of the horses will have been laid off by January 1st, 1920.” —“The Draft-Horse Situation,” in Scientific American, Vol. CXXI, No. 21, page 510; November 22, 1919

Woman Can Eat after Stomach Is Removed

January 15, 1898

“The catalog of brilliant achievements of surgery must now include the operation performed by Dr. Carl Schlatter, of the University of Zurich, who has succeeded in extirpating the stomach of a woman. The patient is in good physical condition, having survived the operation three months. Anna Landis was a Swiss silk weaver, fifty-six years of age. She had abdominal pains, and on examination it was found that she had a large tumor, the whole stomach being hopelessly diseased. Dr. Schlatter conceived the daring and brilliant idea of removing the stomach and uniting the intestine with the oesophagus, forming a direct channel from the throat down through the intestines. The abdominal wound has healed rapidly and the woman’s appetite is now good, but she does not eat much at a time.” —“Living without a Stomach,” in Scientific American, Vol. LXXVIII, No. 3, page 35; January 15, 1898

Thomas Edison Had a Crush on Iron

January 1898

“The remarkable process of crushing and magnetic separation of iron ore at Mr. Thomas Edison’s works in New Jersey shows a characteristic originality and freedom from the trammels of tradition. The rocks of iron ore are fed through 70-ton ‘giant rolls’ that can seize a 5-ton rock and crunch it with less show of effort than a dog in crunching a bone. After passing through several rollers and mesh screens, the finely crushed material falls in a thin sheet in front of a series of magnets, which deflect the magnetic particles containing iron. This is the latest and most radical development in mining and metallurgy of iron.” —“The Edison Magnetic Concentrating Works,” in Scientific American, Vol. LXXVIII, No. 4, pages 55–57; January 22, 1898

Baby Bottles Are the Best Way to Drink in Space

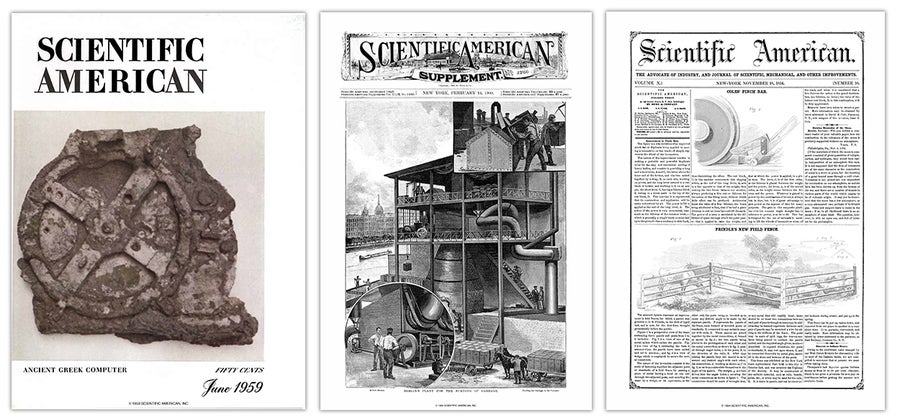

June 1959

“The problems of eating and drinking under weightless conditions in space, long a topic of speculation among science-fiction writers, are now under investigation in a flying laboratory. Preliminary results indicate that space travelers will drink from plastic squeeze bottles and that space cooks will specialize in semiliquid preparations resembling baby food. According to a report in the Journal of Aviation Medicine, almost all the volunteers found that drinking from an open container was a frustrating and exceedingly messy process. Under weightless conditions even a slowly lifted glass of water was apt to project an amoeba-like mass of fluid onto the face. Drinking from a straw was hardly more satisfactory. Bubbles of air remained suspended in the weightless water, and the subjects ingested more air than water.” —“Space Menus,” in Scientific American, Vol. 200, No. 6, pages 82, 85; June 1959

Hypnosis Can Cure Lying but Not Lack of Ambition

February 24, 1900

“Dr. John D. Quackenbos, of Columbia University, has long been engaged in experiments in using hypnotic suggestion for the correction of moral infirmities and defects such as kleptomania, the drink habit, and in children habits of lying and petty thieving. Dr. Quackenbos says, ‘I find out all I can about the extent of a patient’s weakness. For each patient I have to find some ambition, some strong conscious tendency to appeal to, and then my suggestion, as an unconscious impulse, controls the moral weakness by inducing the patient to further his desires by honest means. Of course, if a man has, like one of my patients, no ambition in the world save to be a good billiard player, he can’t be cured of the liquor habit, because his highest ambition takes him straight into danger.’” —“Hypnotism in Practice,” in Scientific American Supplement, Vol. XLIX, No. 1260, page 20192; February 24, 1900

Aliens Could Have 100 Eyes

November 18, 1854

“Sir David Brewster, who supposes the stars to be inhabited, as being ‘the hope of the Christian,’ asks, ‘is it necessary that an immortal soul be hung upon a skeleton of bone; must it see with two eyes, and rest on a duality of limbs? May it not rest in a Polyphemus with one eye ball, or an Argus with a hundred? May it not reign in the giant forms of the Titans, and direct the hundred hands of Briareus?’ Supposing it were true, what has that to do with the hope of the Christian? Nothing at all. This speculating in the physical sciences, independent of any solid proofs one way or the other, and dragging in religion into such controversies, neither honors the Author of religion, nor adds a single laurel to the chaplet of the sciences; nor will we ever be able to tell whether Mars or Jupiter contain a single living object.” —“Inhabitants in the Stars,” in Scientific American, Vol. X, No. 10, page 74; November 18, 1854

New Party Food: Oxygen Cakes

February 2, 1907

“Smoke helmets, smoke jackets, and self-contained breathing apparatus generally are used in mines of all kinds, fire brigades, ammonia chambers of refrigerating factories and other industrial concerns. The curious gear is intended to supply the user with air for about four hours. Oxygen can be supplied from a steel cylinder. Some shipping companies absolutely refuse to carry compressed oxygen in steel cylinders, however. Now a new substance, known as ‘oxylithe,’ has come along. The stuff is prepared in small cakes ready for immediate use, and on coming in contact with water it gives off chemically pure oxygen.” —“Breathing Masks and Helmets,” by W. G. Fitz-Gerald, in Scientific American, Vol. XCVI, No. 5, pages 113–114; February 2, 1907

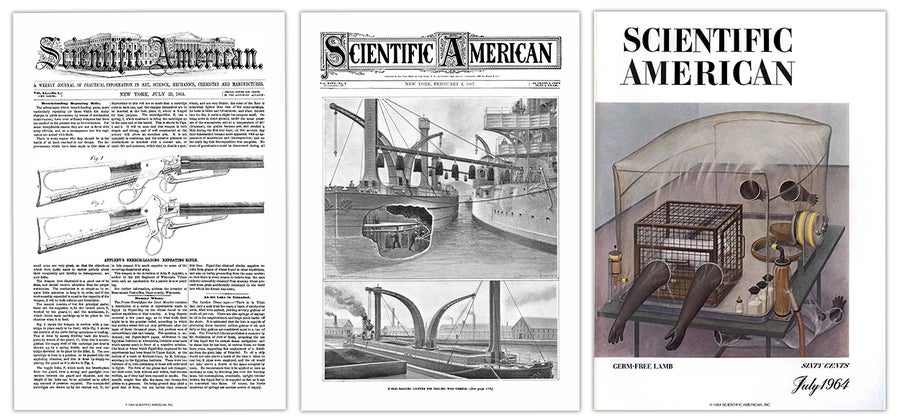

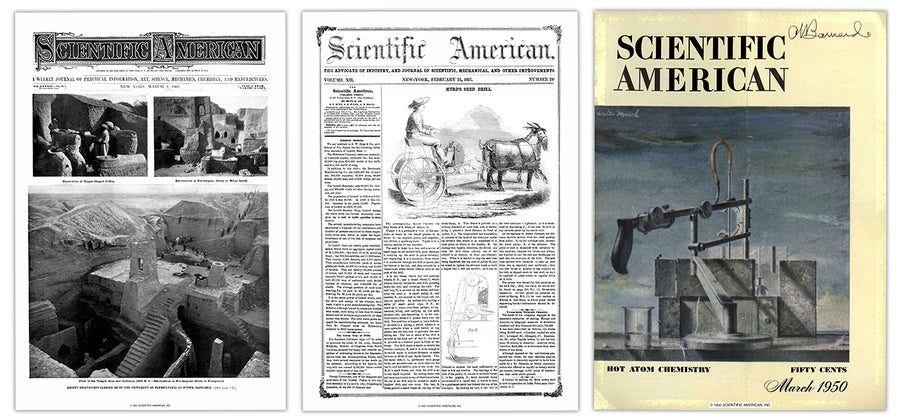

Fake News: Wheat Buried with Mummies Can Grow

July 23, 1864

“There is a popular belief that wheat found in the ancient sepulchres of Egypt will not only germinate after the lapse of 3,000 years, but produce ears of extraordinary size and beauty. The question is undecided; but Antonio Figari-Bey’s paper, addressed to the Egyptian Institute at Alexandria, appears much against it. One kind of wheat which Figari-Bey employed for his experiments had been found in Upper Egypt, at the bottom of a tomb at Medinet-Aboo [Madīnat Hābū]. The form of the grains had not changed, but their color, both without and within, had become reddish, as if they had been exposed to smoke. On being sown in moist ground, on the ninth day their decomposition was complete. No trace of any germination could be discovered.” —“Mummy Wheat,” in Scientific American, Vol. XI, No. 4, page 49; July 23, 1864

First Picturephone Requires an Enormous Pocket

July 1964

“By this month it should be possible for a New Yorker, a Chicagoan or a Washingtonian to communicate with someone in one of the other cities by televised telephoning. The device they would use is called a Picturephone and is described by the American Telephone and Telegraph Company, which developed it, as ‘the first dialable visual telephone system with an acceptable picture that has been brought within the range of economic feasibility.’ A desktop unit includes a camera and a screen that is 43⁄8 inches wide and 53⁄4 inches high. AT&T says it cannot hope to provide the service to homes or offices at present, one reason being that the transmission of a picture requires a bandwidth that would accommodate 125 voice-only telephones.” —“Picturephone,” in Scientific American, Vol. 211, No. 1, page 48; July 1964

Scientific American Returns Bribe Offered by Casino Cheat

March 2, 1901

“A correspondent from the city of Boone, Iowa, sends $5 and some sketches of a table he is building, evidently intended for some gambling establishment. There is a plate of soft iron in the middle of a table under the cloth, which by an electric current may become magnetized. Loaded dice can thereby be manipulated at the will of the operator. He desires us to assist him in overcoming some defects in his design. We have returned the amount of the bribe offered, and take the opportunity of informing him that we do not care to become an accessory in his crime.” —“A Disingenuous Request,” in Scientific American, Vol. LXXXIV, No. 9, page 135; March 2, 1901

That Giant Sucking Sound Doesn’t Exist

February 21, 1857

“I have been informed by a European acquaintance that the Maelstrom, that great whirlpool on the coast of Norway, has no existence. He told me that a nautical and scientific commission, appointed by the King of Denmark, was sent to approach as near as possible to the edge of the whirlpool, sail around it, measure its circumference, observe its action and make a report. They went out and sailed all around where the Maelstrom was said to be, but the sea was as smooth as any other part of the German ocean. I had been instructed to believe that the Maelstrom was a fixed fact, and that ships, and even huge whales, were sometimes dragged within its terrible liquid coils, and buried forever.” —“Maelstrom—The Great Whirlpool,” in Scientific American, Vol. XII, No. 24, page 187; February 21, 1857

Small Jets of Air Make Cats Neurotic

March 1950

“Neurotic aberrations can be caused when patterns of behavior come into conflict either because they arise from incompatible needs, or because they cannot coexist in space and time. Cat neuroses were experimentally produced by first training animals to obtain food by manipulating a switch that deposited a pellet of food in the food-box. After a cat had become thoroughly accustomed to this procedure, a harmless jet of air was flicked across its nose as it lifted the lid of the food-box. The cats then showed neurotic indecision about approaching the switch. Some assumed neurotic attitudes. Others were uninterested in mice. One tried to shrink into the cage walls.” —“Experimental Neuroses,” by Jules H. Masserman, in Scientific American, Vol. 182, No. 3, pages 38–43; March 1950