Mystery tower fossils may come from a newly discovered kind of life

Towering prototaxites ruled Earth before trees—and they may have been a form of life entirely new to science

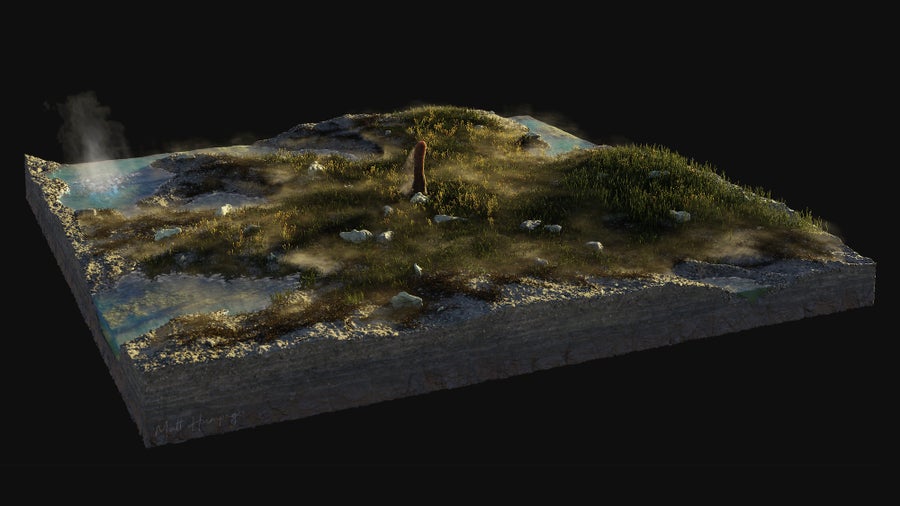

Reconstruction of Prototaxites taiti, which could reach the height of a telephone pole, growing in the 407-million-year-old Rhynie chert ecosystem.

Matt Humpage, Northern Rogue Studios

Before trees came along some 400 million years ago, our planet’s landscape was dominated by enigmatic, spire-shaped life-forms that towered more than 25 feet above the ground. Their trunklike fossils were discovered in 1843. Yet despite more than a century of speculation, scientists have struggled to answer the most basic question about Earth’s original terrestrial giants: What were they?

According to a new study, that may be because they belonged to a previously unknown branch of life.

The first person to examine this biological misfit did so in 1855, and in 1859 he dubbed it Prototaxites, which means “early yew.” The name stuck, even though experts soon realized the organism wasn’t a tree at all. Maybe it was some kind of land-based kelp or a megalithic mushroom? “It feels like it doesn’t fit comfortably anywhere,” says Matthew Nelsen, a senior research scientist at the Field Museum of Natural History, who was not involved in the new study. “People have tried to shoehorn it into these different groups, but there are always things that don’t make sense.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Over time, two main hypotheses emerged: either Prototaxites was an ancient fungus, or it fell into a category all its own. Now, after comparing fossils from these cryptic organisms with fossil fungi from the same rock deposit, the authors of the new study, published today in Science Advances, conclude that Prototaxites was likely a distinct lineage. That would place it on an equal footing with the six currently recognized kingdoms of life: those of plants, animals, fungi, protists, bacteria and archaea.

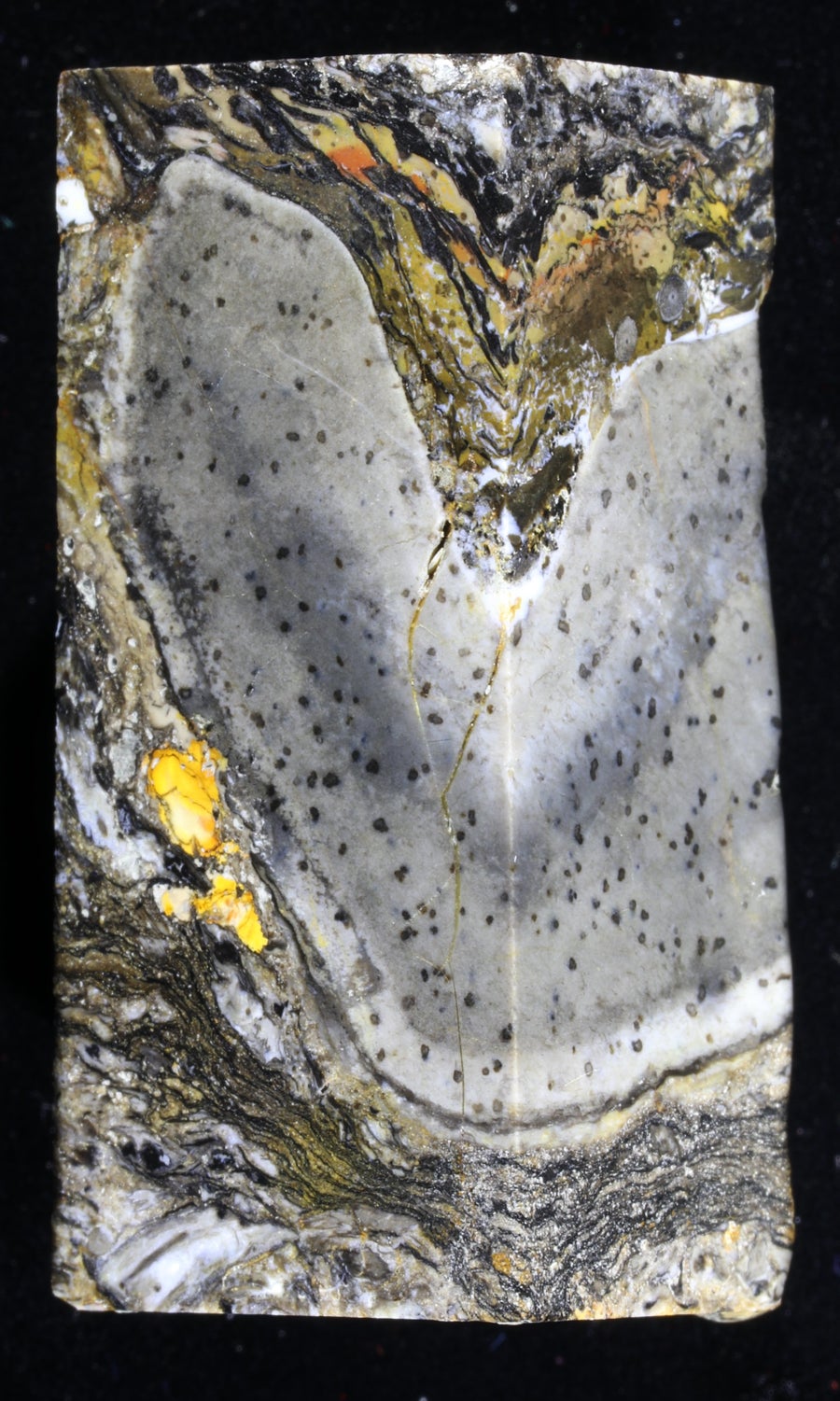

A fossil specimen of Prototaxites taiti shows its spotty internal structure.

Laura Cooper, University of Edinburgh

Prototaxites was composed of interwoven tubes, giving it a superficial resemblance to fungi. But the anatomical similarities end there. The researchers found that Prototaxites’ tubes branched wildly, whereas the threadlike hyphae in modern fungi follow more orderly patterns. Plus, the researchers detected no chemical trace of chitin, a polymer found in the cell walls of all living fungi and in the fossil fungi that were preserved alongside Prototaxites. “It doesn’t seem to have any of the characteristic features of the living fungal groups,” says the study’s co-lead author Laura Cooper, a Ph.D. student at the University of Edinburgh.

This wasn’t totally unforeseen. In a 2022 paper that Nelsen co-authored with paleobotanist Kevin Boyce of Stanford University, the researchers argued that “if Prototaxites was indeed of fungal origin, it may represent part of an extinct lineage”—in other words, it already stood apart from other fungi. Boyce is agnostic about where Prototaxites truly belongs, and he isn’t prepared to cast it out of the fungal kingdom yet. But he notes that even if the organism is merely an oddball fungus, it independently evolved a unique form of complex, multicellular life. “No matter what,” Boyce says, “it’s something weird doing its own thing.”

Prototaxites taiti towers over the surrounding landscape in a paleoenvironment reconstruction of the 407-million-year-old Rhynie chert hot spring ecosystem.

Matt Humpage, Northern Rogue Studios

Cooper argues Prototaxites “was so fundamentally different from the fungi we see today” that “trying to shove it in the fungi is not productive.” Whether or not this study settles the question of taxonomy, there’s much left to learn. Previous work by Boyce shows that Prototaxites probably played an ecological role much like that of fungi: consuming decayed organic matter. But little organic matter was available. In a world of ankle-high plants, these organisms grew tall as telephone poles. “How that actually works energetically,” Cooper says, “is still a complete mystery.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.