Longest-Ever Look at Stormy Region on the Sun Offers New Clues to Space Weather

Scientists observed an active region on the sun for a record 94 days, marking a “milestone in solar physics”

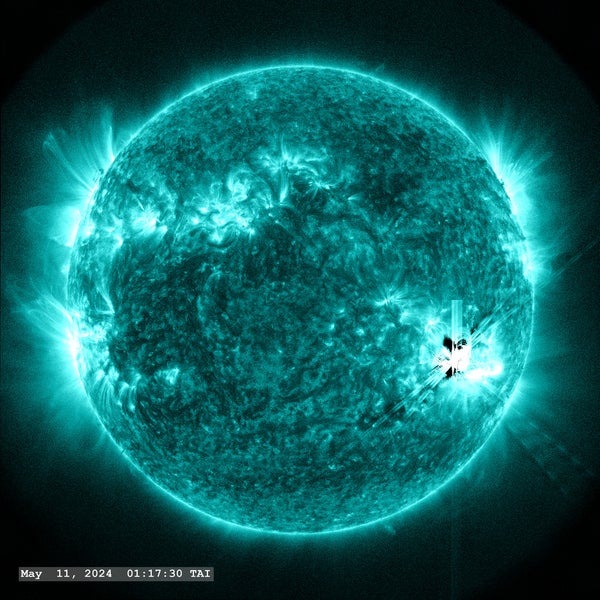

An image taken by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory spacecraft shows a powerful solar flare produced on May 11, 2024, during a spate of activity that was associated with strong auroras.

NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio

May 2024 was a tumultuous month for Earth: Our planet was rocked by some of the worst geomagnetic storms in more than 20 years. Triggered by a slew of solar flares, the storms disrupted satellites, power grids, and GPS and cast the northern lights as far south as Florida.

An active region on the sun, NOAA 13664, was pinpointed as the source of the flares. And on Monday scientists revealed that they observed the region for 94 days, marking the longest-ever look at an active region on the sun.

“It’s a milestone in solar physics,” said Ioannis Kontogiannis, a solar physicist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETH Zurich), who helped lead the effort, in a statement. “This is the longest continuous series of images ever created for a single active region.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The sun’s active regions aren’t easy to observe. Because our home star rotates on an axis, any given region is only visible from Earth for a short period before it spins out of view.

The European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter mission has helped to changed that. Since it set out in 2020, researchers have been able to use it to continuously track active regions, offering insights into how solar eruptions fuel geomagnetic storms on Earth. But scientists still can’t fully predict how big an eruption will be, which can affect planning to help deal with the potential consequences on Earth.

“Even signals on railway lines can be affected and switch from red to green or vice versa,” said Louise Harra, lead author of a study detailing the researchers’ results and a professor of physics at ETH Zurich, in the same statement. “That’s really scary.”

In NOAA 13664’s case, the active region appeared to originate on the far side of the sun on April 16, 2024, wreaked havoc on Earth and died sometime after it rotated out of sight following July 18, 2024, according to the observations. The researchers hope that their data will offer new insights to help scientists better track solar weather and understand the ways it affects our planet.

“We live with this star,” Kontogiannis said in the recent statement, “so it’s really important we observe it and try to understand how it works and how it affects our environment.”

Editor’s Note (1/5/26): This article was edited after posting to better clarify that the active region rotated out of sight after July 18, 2024, and to correct the name of NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory in the image caption.

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.