Breakthrough in Digital Screens Takes Color Resolution to Incredibly Small Scale

These miniature displays can be the size of your pupil, with as many pixels as you have photoreceptors—opening the way to improved virtual reality

Visual displays have steadily gotten smaller and held closer to our eyes as our viewing habits have shifted from cinema screens to TVs to computers, smartphones and virtual reality. This shift has required higher image resolution (usually through increased pixel counts) to provide enough detail. Conventional light-emitting pixels work poorly below a certain size: brightness drops, and colors bleed. The same isn’t true for reflective displays such as those used in many e-readers, whose pixels reflect ambient light rather than emitting their own—but creating those pixels typically requires larger components.

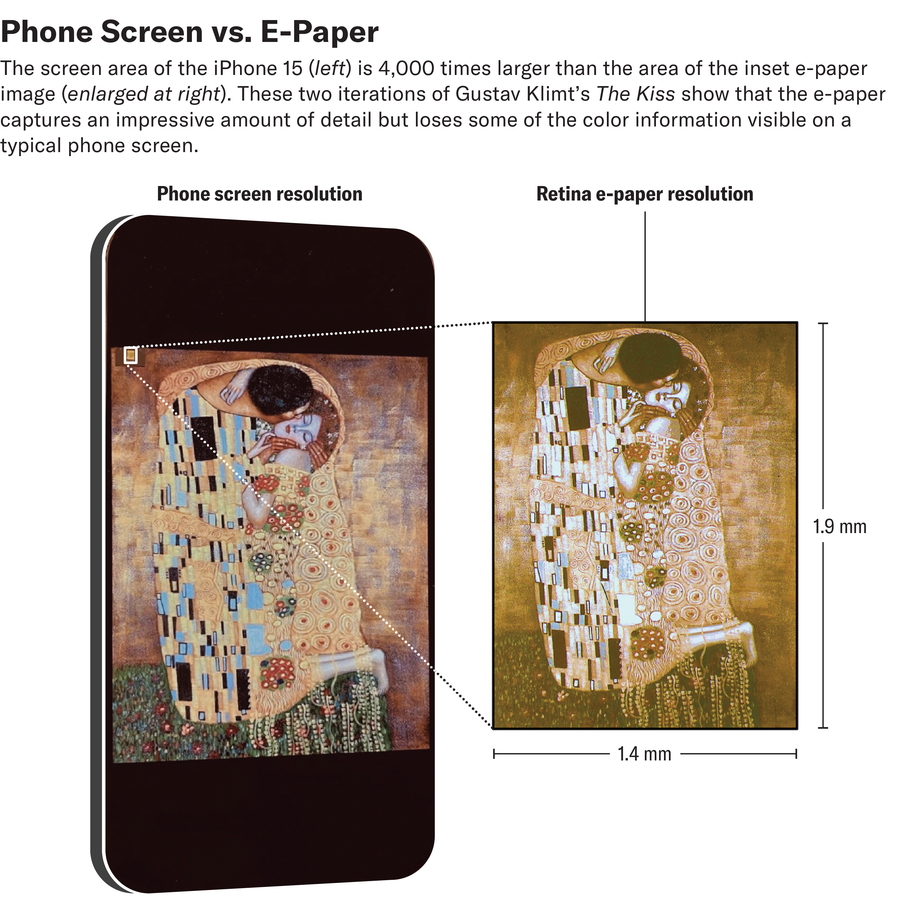

A new reflective display could shatter those restrictions with resolutions beyond the limit of human perception. In a recent study in Nature, scientists describe a reflective retina e-paper that can display color video on screens smaller than two square millimeters across.

The researchers used nanoparticles whose size and spacing affect how light is scattered, tuning them to create red, green and blue subpixels. The material is electrochromic, so its light absorption and reflection can be controlled with electrical signals. With this setup, “metapixels” consisting of the three subpixels can generate any color if you deliver appropriate signals.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Each pixel is only 560 nanometers wide, creating a resolution above 25,000 pixels per inch—more than 50 times that of current smartphones. “We can make displays a similar size as your pupil, with a similar number of pixels as photoreceptors in your eyes,” says study co-author Kunli Xiong of Uppsala University in Sweden. “So we can create virtual worlds very close to reality.”

E-paper screens also have relatively low energy requirements; the pixels retain their color for some time, so power is generally needed only when colors change. “It uses ultralow power,” Xiong says. “For very small devices, it is not easy to integrate large batteries, so that energy saving becomes even more important.”

The team demonstrated the technology with a version of The Kiss by Austrian painter Gustav Klimt and a three-dimensional butterfly image. “People have made these kinds of materials before, but usually they produce poor colors,” says Jeremy Baumberg, a nanotechnologist at the University of Cambridge, who studies how nanoscale materials interact with light. In comparison, the design of Xiong and his colleagues’ subpixels “generates colors that look more compelling than I’ve seen before,” Baumberg says.

These pixels can be rapidly controlled, enabling a reasonable refresh rate—but the necessary electronics for such a high resolution do not yet exist. Xiong and his colleagues anticipate that engineering companies will begin to develop such systems.

Meanwhile Xiong’s team plans to optimize other aspects of the technology such as its speed and lifetime. “Every time you switch [colors], the material’s structure changes, and eventually it crumbles,” Baumberg says—similar to how batteries decay. He estimates that it’ll be five to 10 years before we see commercially available devices.

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.