November 19, 2025

3 min read

After Last Week’s Spectacular Auroras, What’s Next for the Sun?

The sun’s current 11-year activity cycle has already peaked—but extreme outbursts from our star may still be in store

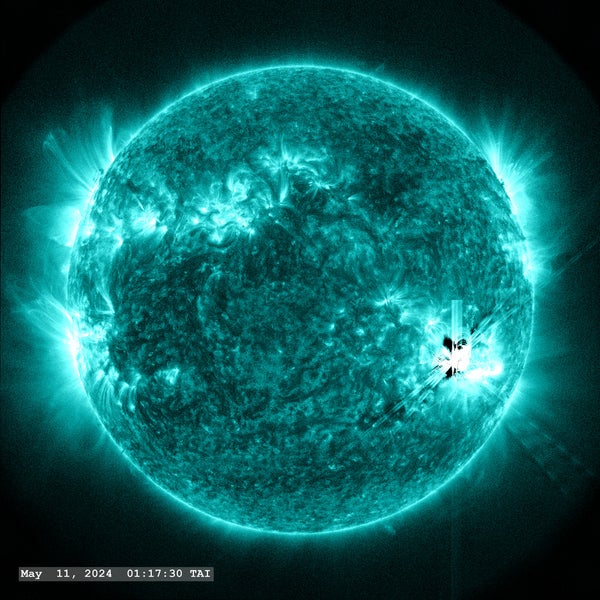

An image taken by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Orbiter spacecraft shows a powerful solar flare produced on May 11, 2024, during a spate of activity associated with strong auroras.

NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio

People in the U.S. were treated to stunning auroras last week when a powerful geomagnetic storm pushed the celestial displays as far south as Florida and Mexico.

The spectacle was particularly enthralling for Lisa Upton, who caught the skies over Boulder, Colo., glowing eerily red. Upton, a heliophysicist at the Southwest Research Institute, is an expert in forecasting the solar cycle—our star’s waxing and waning activity that sets the baseline for auroras and other space weather events. Scientific American asked Upton to explain what we can expect from the sun in the wake of last week’s breathtaking displays.

The sun’s activity rises and falls over an 11-year cycle that is measured by the number of sunspots, dark splotches that dot our star’s surface and that are associated with magnetic storms. The official peak of the current cycle, dubbed Solar Cycle 25, occurred in October 2024. Sunspot tallies have slightly ebbed since then but have remained relatively high.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

At this point, Upton expects sunspot numbers to continue their decline. But solar activity is more complicated than the seeming simplicity of the solar cycle. Although sunspots are associated with solar outbursts, the declining phase of a solar cycle is often counterintuitively associated with more activity than a mere sunspot tally might suggest.

Such activity, also known as space weather events, can include eruptions of high-energy light called solar flares, as well as coronal mass ejections, which are giant blobs of solar plasma and magnetic field blasted into space. When they wash over Earth, such outbursts can damage satellites, jumble communications and navigation technology and interfere with the power grid—reminding heliophysicists (and everyone else) that our star isn’t always so tranquil and innocuous.

These solar outbursts usually originate near sunspots, but not every sunspot is equally likely to make its presence known. Bigger sunspots are more prone to activity, as are those with a complex mess of interwoven positive and negative polarities. Large, messy sunspots that mingle or merge are especially fertile sites for flare-ups. “When they start interacting with each other, they’re more likely to get tangled up and become eruptive,” Upton says.

Such interactions are more common in the wake of maximum solar activity than as it approaches because sunspots that occur near the end of solar maximum tend to do so closer to both the equator and each other than those that occur earlier in the cycle do.

Because of that trend, Upton isn’t ready to rule out additional fireworks from the sun, even as the solar cycle starts to quiet down.

Such activity may even come from the very same sunspot that caused last week’s displays, which scientists dubbed active region 4274 (AR4274). Our star’s rotation has now carried this sunspot to the sun’s far side and thus out of firing range—but the active region may well survive the two-week trek to face Earth again. (Scientists will be monitoring its size using a technique called helioseismology, which analyzes the sound waves that pass through the sun to map sunspots that are invisible to Earth.)

“I expect we’ll see it come back,” Upton says. “The ultimate question is whether it will continue to grow when it’s on the far side or if it’ll settle down.”

Even in the longer term, the solar cycle may still have surprises left in store. Upton notes that within each 11-year cycle, a shorter one-to-two-year cycle drives smaller upticks in activity. And these modest increases can be particularly noticeable during solar cycles of below-average activity, such as the current one. That means Upton will be watching for a small burst of activity in a year or two—although it’s unlikely to match what the sun has produced in recent years.

Nevertheless, this solar cycle is on its way out, with sunspot numbers expected to further dwindle toward a solar minimum around 2030 or 2031. But even if the sun’s fireworks are on hiatus, for Upton and her colleagues, the excitement continues.

“The declining phase is my favorite time of the solar cycle,” she says, “because that means it’s time to start predicting the next cycle”—and then, of course, to see how real activity compares with those forecasts. “The sun always loves to surprise us.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.