Rob, 42, is a fitness guy. He loves working out, spends his spare time in the jujitsu gym and eats a high-protein diet heavy on avocado oil. He cares about his health and wants to optimize it, and a lot of the social media influencers he follows are the same.

So a few years back, when Rob started seeing ads for testosterone replacement therapy—TRT—pop up in his feeds, he was intrigued. (Names of patients in this story have been changed to protect their privacy.) Rob was already a man in good shape. But testosterone sounded like a great way to get an extra edge.

“I bought into what I was listening to on social media, which is, ‘You’re going to feel better, you’re going to get stronger, and you’re going to look better,’” he says.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Rob went to a local, privately owned clinic. There he got a blood test, which revealed that his testosterone was well within normal range. “I certainly didn’t need TRT,” he says.

The clinic prescribed it anyway.

Rahim, 48, tells a similar story. He walked into a men’s health clinic a decade ago looking for an energy and fitness boost. He got an injection that very day. On subsequent visits the clinic pushed his dose higher and higher, but he perceived little benefit. “I just felt like I was taken advantage of,” he says now. “I felt like somebody was using my body to make money.”

Testosterone therapy—prescription supplements in the form of pills, patches, injections or implantable pellets—has probably never been more publicized or popular. Podcaster Joe Rogan is on it. On Reddit and on TikTok, on highway billboards and in TV commercials, you’ll see testimonials in praise of TRT promising mood boosts, better sex, extra energy and quite possibly an abdominal six-pack. The global market has been estimated at $1.9 billion.

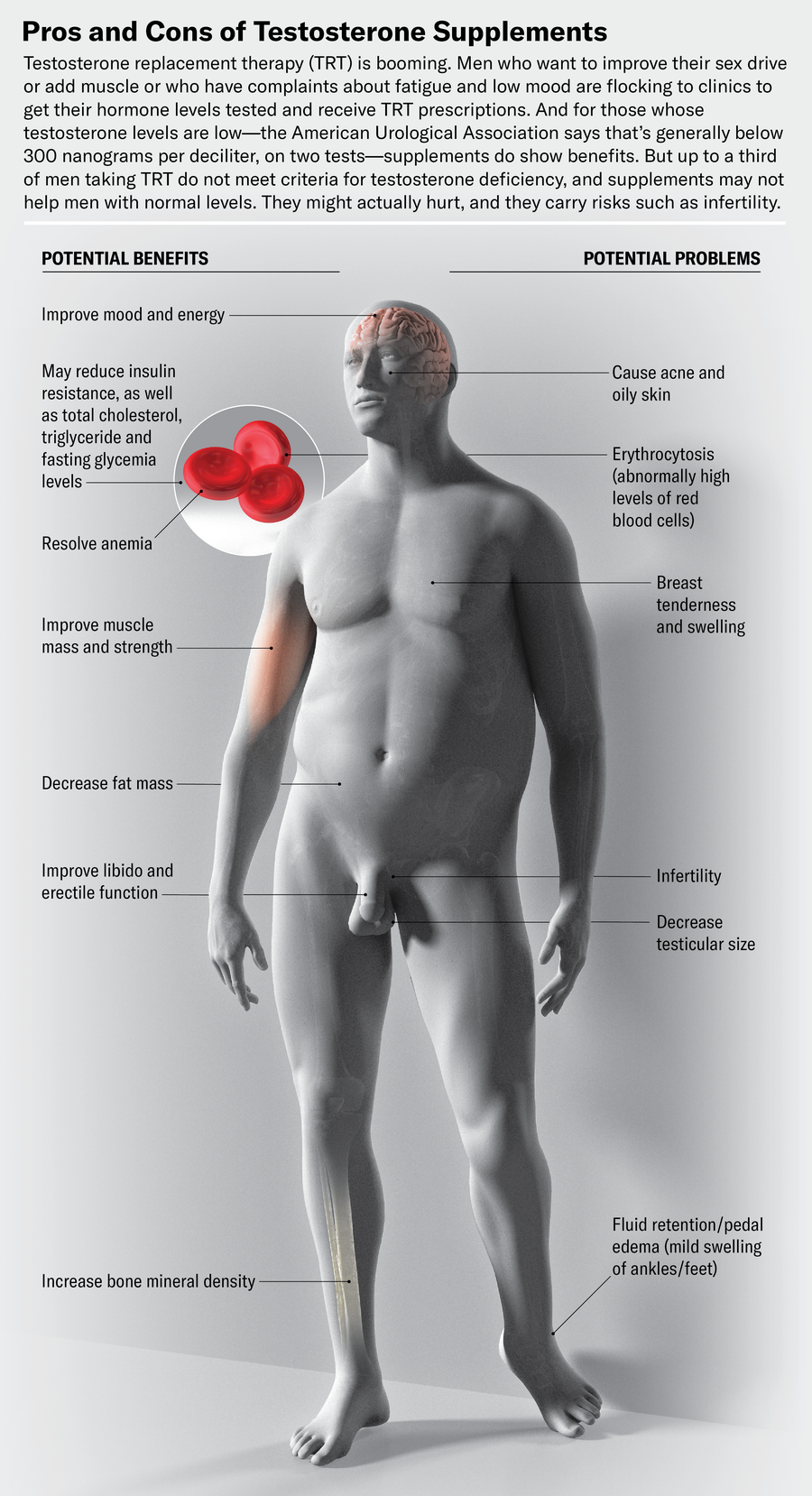

For the right men, usually those with seriously low levels of the hormone, TRT can improve mood, energy levels and sex drive. It can increase muscle, decrease fat and lower levels of biomarkers for heart disease. Rigorous studies have dispelled once common medical concerns that the supplements increase the chance of prostate cancer; they don’t. And many responsible clinics that prescribe TRT inform their clients of the potential risks and benefits and monitor them closely.

But many men getting supplements may not have low testosterone to begin with, and for them, boosting levels of the hormone even higher could cause harm. There is a lot of medical disagreement about what constitutes “low,” driven by several studies with different populations and different cutoffs. Because of this uncertainty, some clinics will legally prescribe TRT for men whose hormone levels are, according to many measures, just fine. “It will not make you live longer. It will not make you otherwise healthier,” says Channa Jayasena, who is a reproductive endocrinologist at Imperial College London.

And TRT carries risks. Supplemental testosterone can increase the chances of infertility and shrink testicles. It can lead to an abnormal blood condition called erythrocytosis. It is also associated with heightened rates of acne and painful swelling of male breast tissue. So urologists and endocrinologists who study the hormone caution men thinking about TRT to proceed very carefully.

Thanks to its inexorable cultural ties to masculinity, testosterone is perhaps more prone than other “wellness” treatments to emotional appeal. The TRT ads that show up on social media promise a lot but rarely mention side effects or proper testing. “The majority of the testosterone information on TikTok and Instagram is horrible, horrendous,” says Justin Dubin, a urologist at Memorial Healthcare System in southern Florida. “It’s not accurate.”

The normal range for testosterone level is broad, spanning from around 300 to 1,000 nanograms per deciliter of blood (ng/dl). After about age 40, a person’s amount of circulating testosterone starts to decline by approximately 1 percent a year, and with the U.S. population getting older, it’s no surprise that interest in TRT is rising. There is also some evidence that average levels of testosterone are dropping in young men. Diseases that have become more common, such as obesity and diabetes, affect hormone production and likely explain some of that decline.

But interest in boosting testosterone goes way back—back to before anyone knew what testosterone was. In 1849 German scientist Arnold Adolph Berthold observed that castrated roosters showed little interest in fighting over females. When rooster testes were transplanted into these peaceniks, they suddenly developed an interest in sex and barnyard brawling.

Doctors soon sought to harness the testes’ miraculous masculinizing power. In 1889, 72-year-old Mauritian neurologist Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard injected himself with a slurry of crushed-up dog and guinea pig testicles, seeking rejuvenation. He reported that after a few injections he could sprint down stairs like a young man and stand at his laboratory table for hours.

Violet Frances; Source: Abraham Morgentaler (scientist reviewer)

Russian-born physician Serge Voronoff tried transplanting testicles from monkeys into people and gushed about his results in his 1925 book, Rejuvenation by Grafting. He wrote of one 74-year-old patient that after surgery, “his superfluous fat had disappeared, his muscles had become firm, he held himself erect and conveyed the impression of a man in perfect health … The grafting had transformed a senile, impotent, pitiful old being into a vigorous man, in full possession of all his faculties.”

Today doctors say any positive effects from these treatments were pure placebo. In 2002 Australian researchers tried making Brown-Séquard’s testicle extracts and found that the amount of testosterone in the preparations was a quarter of what would be needed to produce a biological response. And in the days when Voronoff worked—before modern tissue-preservation advances or any understanding of antirejection drugs—testicle transplants (especially cross-species transplants) would have been incredibly unlikely to survive.

A synthetic form of testosterone was developed in 1935, making a drug form of TRT possible. But its advent did not lead to a prescribing boom right away. (It did catch the notice of bodybuilding communities, who began asking for it.) In part, the medical reluctance was because of a small 1941 study showing that adding testosterone made prostate cancer grow faster and that the tumors shrank when levels of the hormone were low. The connection made doctors extremely wary of treating men with testosterone—even men with undeniable hypogonadism, meaning their testes could not make sufficient amounts of the hormone. “There was a near-complete prohibition,” says Abraham Morgentaler, a urologist and testosterone researcher at Harvard Medical School.

In the 1980s Morgentaler, who had investigated the effect of testosterone on the reproductive behavior of lizards as a student, was a young urologist specializing in male infertility, treating patients with low testosterone, erectile dysfunction and a lack of libido. They were desperate. Morgentaler thought back on his lizards, which had failed to woo females when deprived of testosterone. Cautiously, he began to dose a few of his patients with the hormone. Not only did they report improved sex lives, he says, but “they described to me how they felt better outside of their sexual symptoms—things like ‘I’ve never had so much patience for my small children,’ ‘I wake up in the morning, I swing my legs over my bed, I’m optimistic about my day.’”

As Morgentaler continued his hormone-treatment research, he failed to see any increase in prostate cancer growth in patients. Over time the evidence that testosterone does not necessarily supercharge prostate tumors has piled up. By the early 2000s fears of prostate cancer with testosterone treatment were easing, if not altogether disappearing.

As a result, TRT began to rise in popularity, and its use increased more than threefold between 2001 and 2011, according to research published in 2013. Still there was hesitation. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a warning in 2014 that TRT might raise the risk of heart attacks and strokes. Testosterone influences muscle growth and activity; muscle fibers are dotted with many androgen receptors. The heart, of course, is a muscle. In men who take anabolic steroids for bodybuilding—natural testosterone is a form of this type of hormone—heart problems are a known consequence.

To tackle these two safety issues, a consortium of researchers put together the TRAVERSE trial, the largest-ever randomized, controlled trial on TRT for men with low testosterone. They screened more than 5,000 men, aged 45 through 80 years, to ensure participants had low levels of prostate-specific antigen (or PSA, a marker of prostate cancer) at the onset of the study, and they followed the men for an average of three years. In 2023 the researchers reported the results. There was no increase in prostate cancer with testosterone treatment. Nor was there an increase in strokes, heart attacks or cardiovascular deaths.

That’s the good news for men interested in TRT: for those with low testosterone and normal PSA levels who get boosted into the average range for testosterone, the risk of cancer or heart problems is low. But TRT remains controversial, largely because there is no consensus on how to define “low testosterone.” The American Urological Association guidelines suggest that as a rule of thumb, “low” means a total testosterone level under 300 ng/dl, as measured twice on different mornings (because testosterone levels fluctuate). But an international group, the Endocrine Society, has a “normal” range—between 264 and 916 ng/dl—that partly overlaps with that category. The European Academy of Andrology guidelines put the “lower limit of normality” between 231 and 350 ng/dl. One reason for these disparities is that testosterone levels can swing by 100 ng/dl or more in a single day, so symptoms (fatigue, for instance) can correlate with very different numbers.

The TRAVERSE trial used a cutoff of 300 ng/dl for “low.” When men who had lower levels received supplements, there were clear benefits for mood and energy. In 2024 researchers reported a 50 percent increase in sexual activity among men with low testosterone from TRAVERSE who were treated with hormone supplements. That translated to an increase of almost one additional sexual “event” per day—a category that included partnered sex, masturbation, daydreams, flirting and spontaneous erections. A comparison group that got a placebo had only a 25 percent increase.

Less clear are the effects of TRT on the fuzzier symptoms sometimes ascribed to low testosterone, such as fatigue, brain fog, depression and irritability. Joe, 38, says he was in a pretty low place when he learned, in his early 30s, that his level was only 95 ng/dl. He started TRT that keeps him above 600, and he says it works. “It just helps me feel incredibly normal,” he says. The TRAVERSE trial found no benefit of TRT over a placebo for addressing low-grade depressive symptoms. But it did find improvements in both mood and energy in men with significant depression, according to another 2024 study. There was no benefit for cognition or sleep.

Doctors say that every month they treat multiple men who haven’t been warned that their testosterone regimen will crater their sperm count.

Men in the borderline-low range, with levels around 300 ng/dl, haven’t been studied systematically, says Frederick Wu, an emeritus professor of medicine and endocrinology at England’s University of Manchester who led the European Male Aging Study (EMAS), a very large study of aging men. And for men with normal-range testosterone, the results of TRT might not be as dramatic as they are for men with uncontested low levels. Symptoms such as low energy are particularly difficult to tie to testosterone. Any of the minor insults of midlife can cause fatigue and irritability: young kids who don’t sleep, a sedentary computer job, stress, a poor diet. One of the first things urologists or endocrinologists do when a patient comes in with these symptoms is check for sleep apnea, which can cause brain fog and fatigue while also reducing testosterone. “Testosterone is a very robust indicator of general health status,” Wu says. “If you find low T in a patient, then it is imperative to investigate their general health status rather than having a knee-jerk reaction of starting testosterone treatment.”

There are also almost certainly symptom differences in the way individual men respond to particular hormone levels. “It’s possible that a man with a total testosterone of 350 ng/dl might be deficient in certain ways,” says Joshua Halpern, chief scientific officer at fertility clinic Posterity Health and an adjunct professor of urology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. “Different tissues and organ systems in the body require different levels of testosterone to function optimally.”

Herein lies another area of disagreement. Some doctors argue for trying testosterone only after other health interventions because changes in exercise and diet can boost testosterone and improve general health. Others, such as Morgentaler, argue that TRT can be offered first to men with low levels because supplements could give a man with low energy the boost he needs to start working out and eating better. This argument may now be complicated by the arrival of GLP-1 drugs, such as Ozempic, which make losing weight a lot easier. Should a man with obesity and low testosterone be offered TRT or Ozempic? It’s a question that hasn’t been studied.

A final uncertainty is what type of testosterone measurement to use. Most studies have looked at total testosterone, a measure that captures all of the hormone circulating in the blood. But a lot of that testosterone is bound to other proteins, such as albumin and sex-hormone-binding globulin (SHBG). The hormone sticks tightly to SHBG, and in that state it can’t be used by body tissues. “Free” testosterone, which isn’t bound, can. Ultimately, the amount of free T might be a lot more important than total testosterone when it comes to how men feel. “Symptoms follow free T,” Morgentaler says. In a 2018 study using EMAS data, researchers found that in obese men who developed hypogonadism, only those whose free testosterone dropped alongside their total testosterone actually experienced symptoms. Still, medical societies have no specific free-T cutoffs for treatment, so a doctor’s judgment plays a large role in determining how to use the numbers.

None of these medical debates is likely to come up, however, when people walk into one of the many men’s health clinics. Like Rob or Rahim, they’ll probably be offered a prescription. In 2022 Dubin, Halpern and some of their colleagues published a study in JAMA Internal Medicine for which they went undercover, sending Dubin’s own testosterone measurements to seven men’s health clinics. Dubin’s level happened to be 675 ng/dl, above what most urologists aim for when treating low-T men. In addition, he told the clinics that he hoped to have children in the future. This statement should have stopped them cold. Testosterone is part of the feedback loop that regulates sperm production; if levels of the hormone stay high in the bloodstream, the testes stop making their own testosterone and sperm. “There was really no situation in which I was a good candidate for TRT,” Dubin says.

Six of the seven clinics offered him TRT anyway. This outcome isn’t unusual. “Looking back, it was so ridiculous,” Rahim recalls of his own same-day testosterone initiation. Although professional guidelines universally agree that men should be tested at least twice before starting TRT, a single test seems common for online and private clinics. Rahim’s numbers were in the high 300s, he recalls, but he was soon put on a dose of testosterone so high that it caused side effects, for which the clinic offered to prescribe more medications. “It was in their best interests to inject me with more T because it was better for their revenue, even though it wasn’t necessarily better for my health,” he says.

Other men report similar experiences. John, 42, was in his mid-30s when he sought out TRT, motivated to keep up in the military special-operations job he had at the time. He was prescribed implantable testosterone pellets, which made his total testosterone level shoot up to more than 1,800 ng/dl. He then dealt with a mandibular disorder from clenching his jaw, as well as benign prostate enlargement that required a cascading series of prescriptions.

Morgentaler says that these cases are cautionary tales that men should take seriously. Avoid clinics that offer TRT without first taking a baseline test, he says, or those without a clear follow-up plan for monitoring bloodwork. One 2015 study found that less than half of men on TRT in a large metropolitan health center ever got a follow-up blood test. And that could be a problem because one common side effect of TRT is erythrocytosis, which results in the overproduction of red blood cells.

An ethical clinic should also be honest about TRT’s effect on fertility. Dubin and Halpern say that every month they treat multiple men who haven’t been warned that their testosterone regimen will crater their sperm count. Online influencers often shrug off fertility side effects as short-term, but doctors say they can persist. It can take up to two years after cessation of TRT for men to recover a regular sperm count, according to a 2006 study in the Lancet. As any couple going through infertility struggles can attest, two years is a long time.

Two medications that doctors prescribe to hasten sperm-count recovery, human chorionic gonadotropin and clomiphene citrate, often aren’t covered by insurance and can have their own side effects. Sperm quality may not be as high in men who have recovered post-TRT compared with men who never took testosterone replacement, Halpern says.

Finally, although the TRAVERSE trial suggests that men trying TRT aren’t putting themselves at undue risk of prostate cancer or heart problems, there was a small but unexplained rise in bone fractures in men on the treatment. In addition, there are no studies looking at the impacts of TRT over several decades—and a man starting TRT in his 30s may well be committing to 40 or 50 years of treatment if he doesn’t want to go through the hormonal crash of quitting.

One concern from studies of heavy users of anabolic steroids is that natural testosterone production might not fully recover after long-term use, says Harrison Pope, a Harvard Medical School psychiatrist who has studied anabolic steroid use. A 2023 study in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism looked at men who had used anabolic steroids illicitly. These people reported a lesser quality of life two years after quitting compared with men who had never used them. In the body, these steroid drugs have effects that are similar to testosterone supplements, so the study results raise worries about TRT.

“If you had interviewed me 20 years ago, I would have assured you that if you’d been taking testosterone for a long time, if you stop, the system will rebound and you will go back to normal,” Pope says. “In some cases, I would have been dead wrong.”

For some men it will be worth the risk. Rob, John and Rahim are all on lower doses of testosterone now and being treated by practitioners they trust. They all see benefits in mood, muscle building and energy. But all three feel some ambivalence about the experience. It’s a hesitation about TRT shared by a lot of medical professionals. “There are still many unknowns when it comes to testosterone deficiency,” Halpern says, “including even the basics.”