Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., recently announced that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration will launch a review of the safety of the abortion pill, mifepristone. Health researchers say they’re concerned that the review will be politicized and based on flawed reports. More than 100 studies published over the past few decades have shown that the drug, which was approved by the FDA in 2000, is safe and effective at ending a pregnancy.

Given Kennedy’s history of misrepresenting scientific evidence about vaccines, autism and Tylenol, some scientists say they worry that the health secretary will base the FDA report on unreliable sources.

“Based on what we have seen from this administration to date,” says Peter Lurie, the FDA’s former associate commissioner for public health strategy and analysis, “there is every reason to fear that this study will be a cherry-picking, data-contorting exercise designed to support a predetermined conclusion of lack of safety.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In a statement to Scientific American, Department of Health and Human Services spokesperson Emily Hilliard said the agency “is conducting a study of the reported adverse effects of mifepristone to ensure the FDA’s risk mitigation program for the drug is sufficient to protect women from unstated risks,” echoing an earlier statement from HHS spokesperson Andrew Nixon.

Kennedy has frequently promoted the FDA review when addressing conservative critics who are impatient for the Trump administration to outlaw or dramatically limit abortion. Antiabortion groups were infuriated by the FDA’s recent approval of a second generic version of mifepristone.

In a post on the social media site X, Kennedy pledged to “review all the evidence—including real-world outcomes” for mifepristone, which is currently used in almost two thirds of abortions in the U.S.

Kennedy has provided no timeline for the review’s release and few details about what it will encompass. But in a September 19 letter to state attorneys general, Kennedy cited a report from the Ethics and Public Policy Center, a conservative think tank, that claims mifepristone is more dangerous than FDA analyses suggest and calls for ending telehealth prescription of the drug. The availability of mifepristone via telehealth has contributed to an increase in abortion nationwide in spite of total bans on abortion in 12 states.

That report has serious methodological flaws, says Ushma Upadhyay, a professor of reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco, who dismisses it as “junk science.” She notes that the think tank report was neither peer-reviewed nor published in an established medical journal. The report also does not disclose the specific source of its data, which makes it impossible for other scientists to verify or try to reproduce its findings, she adds. In addition, it provides a false picture of mifepristone’s safety by misclassifying routine follow-up procedures as “serious adverse events,” Upadhyay says.

Kennedy has signaled that the president will be making final regulatory decisions about mifepristone. At a Senate budget hearing in May, Kennedy told lawmakers that “the policy changes will ultimately go through the White House, through President [Donald] Trump.” He said the think tank report “indicates that, at very least, the [drug] label should be changed.”

“Cherry-Picking” Evidence

Some scientists are concerned about Kennedy’s role in the review. When talking about autism and vaccines, Kennedy has often bolstered his arguments with “questionable sources that merely look real,” says Timothy Caulfield, research director at the Health Law Institute of the University of Alberta, who studies health misinformation. “He seems to do this mostly with wedge issues—vaccines, abortion, etcetera—that play to a political agenda.”

Kennedy has succeeded in raising doubts about the safety of proven interventions, including Tylenol, Caulfield says. “Doubt mongering is a very effective strategy, especially in the health space,” he says. “Once that doubt is present, it can have a large impact on the public’s health beliefs and behaviors.”

Kristan Hawkins, president of Students for Life of America, a leading antiabortion group, said in a statement on the group’s website that the FDA review “represents an historic opportunity” to reduce the use of the abortion pill “if handled thoroughly.” The group wants the FDA to conduct an “original investigation” rather than review published studies. It claims that there’s not enough evidence to show that the availability of mifepristone by mail is safe and that previous studies on the drug were written by people who favor wide distribution of the pill.

The Center for Reproductive Rights, a nonprofit global human rights organization that advocates for abortion access, filed a lawsuit in September against the HHS and the FDA in an attempt to force the Trump administration to reveal the process and sources it will use to review mifepristone’s safety. “The public deserves to know what and who is behind decisions being made about their health and access to vital medications,” says Liz Wagner, a senior federal policy counsel at the organization.

Misleading Statistics

Basing the FDA review on the conservative think tank’s report on mifepristone would produce misleading results, Upadhyay says. A wealth of research has found mifepristone to be safe—so safe that the FDA under the Biden administration began allowing it to be dispensed via telehealth instead of requiring that pregnant people see doctors in person. Prescribers and pharmacies must meet special certification requirements to dispense the drug, and pregnant people are required to sign a patient agreement, Upadhyay says.

“If the FDA were to do an actual review based on gold-standard science, I think they would actually end up removing the barriers that remain on mifepristone,” she says.

The think tank report found that 4.7 percent of women who use mifepristone make abortion-related trips to the emergency room. But Upadhyay says this is misleading: many pregnant people who take mifepristone at home go to the emergency room simply to ask if the amount of bleeding they’re experiencing is normal. Others go to the ER to confirm that the abortion was effective, given that over-the-counter pregnancy tests aren’t reliable until four to five weeks after termination, she says. Research shows that only about half of postabortion ER visits lead to medical treatment, Upadhyay says.

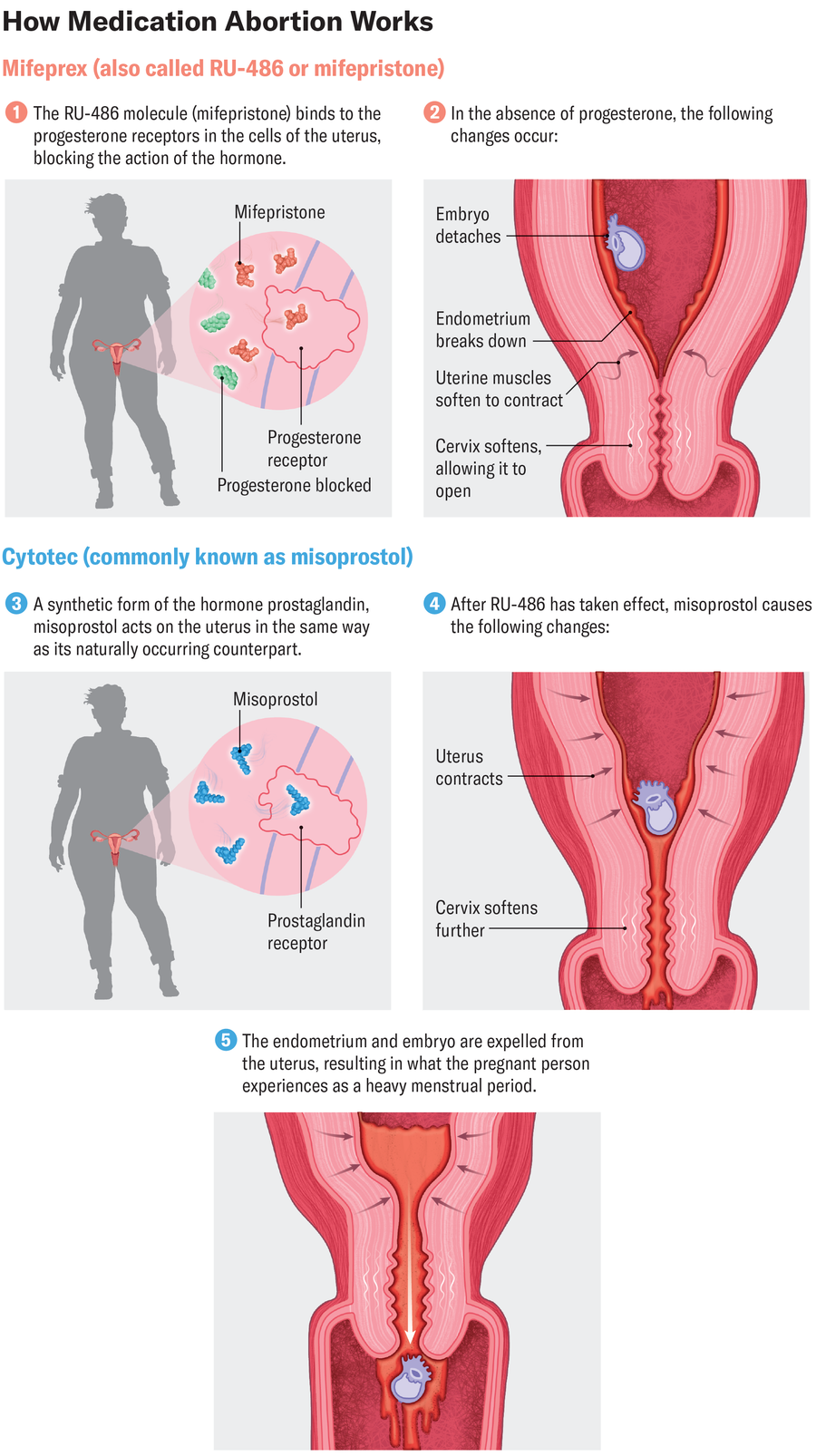

One of mifepristone’s risks is sepsis —a life-threatening condition in which the body’s immune system overreacts to an infection, according to the Ethics and Public Policy Center report. Yet the report finds that the risk of sepsis is just 0.1 percent, a rate even lower than that listed on mifepristone’s label. The report uses this statistic and others to argue that the FDA should require people who are prescribed mifepristone to make “at least three in-person office visits,” including a first visit to receive the mifepristone, a second visit two days later for a dose of misoprostol (a medication used to complete the abortion) and a third visit two weeks later for follow-up. These visits were required when the pill was originally approved in 2000.

The think tank report “would not hold up in any medical or public health journal,” says Jessica Mitter Pardo, a family medicine physician and abortion care provider in New York City and a fellow with Physicians for Reproductive Health, an advocacy group. Yet it might be “used to influence this country’s public health policy and medicine,” she warns.

A Delaying Tactic?

Trump’s record on abortion has been mixed, leaving some to wonder how his administration will handle the mifepristone review.

The president takes credit for appointing the Supreme Court justices who overturned Roe v. Wade, the landmark decision that had protected the right to abortion. Trump won praise from conservatives in January when he pardoned antiabortion activists who were arrested for blocking the entrances of reproductive health clinics. And in August the Trump administration proposed barring doctors at the Department of Veterans Affairs from performing abortions, even in cases of rape and incest, with an exception only to save a pregnant person’s life.

By commissioning the FDA to review mifepristone’s safety, “it’s possible that the Trump administration is laying the groundwork for changes to the mifepristone rules, especially because all but two GOP senators signed a letter asking the FDA to remove mifepristone from the market,” says Mary Ziegler, a professor at the University of California, Davis, School of Law, who studies the history of abortion.

The Trump administration has not publicly committed to changing mifepristone’s use, and it has taken several actions that have upset antiabortion groups.

In May the Department of Justice asked a judge to dismiss a lawsuit from Idaho, Kansas and Missouri that aims to restrict mifepristone use, arguing that the states did not have standing to bring their case in a Texas court.

And during his presidential campaign, Trump said that he does not support a federal abortion ban. Almost two thirds of adults say abortion should be legal in most cases. Voters in 13 states have supported initiatives to keep abortion legal, sometimes by enshrining abortion rights in their state constitution and other times by rejecting proposals to curtail abortion.

Commissioning an FDA review of mifepristone could be a delaying tactic meant to deflect criticism from antiabortion groups without triggering a backlash from voters who support reproductive rights, says David S. Cohen, a professor at Drexel University’s Thomas R. Kline School of Law.

Trump may be especially leery of antagonizing voters who care about abortion—both on the right and the left—before next year’s midterm elections, Ziegler says.

“It’s possible that this is just the Trump administration trying to get antiabortion people to leave them alone,” Ziegler says of the mifepristone review. The study could just be a stalling tactic to buy more time, she suggests. “There’s no reason not to think this study couldn’t last three years.”